“The Secret of Snow”- Tina Harness

On August 1st, I had the incredible opportunity to attend a meeting with Tina Harnesk—the author of the novel “The People Who Sow in Snow”—which took place in Kalix, Sweden.

Tina Harnesk in traditional Sámi clothes

At the event, Tina shared more in-depth details about her debut novel, the writing process, Sami culture and history, and—perhaps most exciting of all—her personal thoughts and emotions as a Sami descendant. The author herself doesn’t speak the Sami language, but she understands it. Her brother, however, does speak it and is even involved in reindeer herding—a traditional livelihood of this ancient and mystical people.

When we talk about colonialism, we usually think of faraway lands, conquests, and empires. But Europe also has its own dark chapters in the history of colonialism—one of them is that of the Sami in Scandinavia.

The Sami are the indigenous people of the northern parts of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia. They have a rich culture, language, and way of life primarily connected to reindeer herding, fishing, and hunting. Despite this, they have been subjected for centuries to assimilation, discrimination, and—though rarely discussed—forced displacement.

The most significant instances of organized displacement of the Sami in Sweden occurred in 1919 and 1928. The reason was the signing of agreements between Sweden and Norway that restricted the Sami’s right to migrate with their herds from northern Sweden to grazing lands in Norway—an integral part of their nomadic way of life.

After the dissolution of the Swedish-Norwegian union in 1905, Norway began restricting Sami access to its territories. The Swedish government decided to “relocate” some Sami communities to the south, to areas like Jämtland and Dalarna. Officially presented as a “necessary measure,” in reality, this was forced displacement from their traditional lands—a process that deeply impacted many generations.

⸻

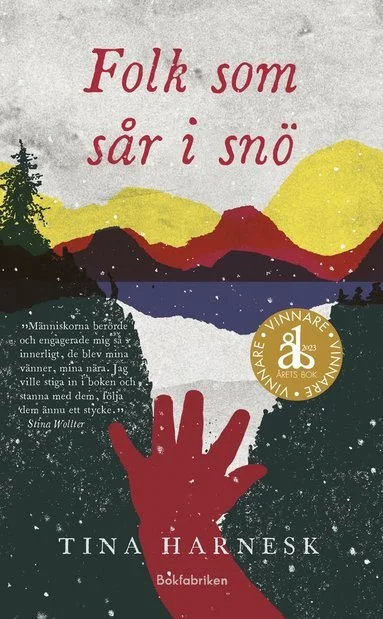

In “The People Who Sow in Snow” (original Swedish title: “Folk som sår i snö”)—named Sweden’s Book of the Year in 2023—we meet Maridja, who has just learned she doesn’t have much time left in this world. She is an eccentric elderly lady, a proud representative of the indigenous northern Sami people, who has no intention of conforming to anyone or anything. Her only goal is to hide her condition from her husband Piera, who is increasingly lost in his own memories.

Sami tradition holds that large families should be created so that elders are cared for. But Maridja and Piera have no children—or at least, that’s what they think. There was once a child they loved more than anything—Heajka-Joná—but he was taken from them. And Maridja is willing to do whatever it takes to find him. In the meantime, she takes on another mission: to find someone who will care for Piera when she is no longer alive.

The elderly woman receives invaluable help from the helpful Siri (or “Sire,” as Maridja endearingly calls her 😊), who speaks through that strange machine called a phone. At the event, the author shared that she herself spoke a lot with Siri to make the dialogues between the assistant and Maridja feel authentic.

The brave Sami woman is convinced that in order to find the now-grown Heajka-Joná, she needs to attract the attention of as many people in uniform as possible—even if that means burning down a barn or shooting a moose…

I haven’t read the book in Bulgarian, but the language and style in the Swedish original are captivating—ironic, multi-layered, with that kind of humor that makes you laugh through tears. A rich palette of characters and complex family ties keep you hooked until the very end—you don’t want to put the book down until you’ve unraveled all the secrets.

Tina Harnesk speaks with great tenderness about her characters. Maridja, for example, is a composite image of many women in her life. Mimi was inspired by Moominmamma. And her relationship with Kaisa is particularly complex and problematic. She even wrote letters to him to figure out what her issue with him was. :)

The writing process was chaotic, but very productive. Harnesk wrote the book in about three months because, as she says, the characters “kept talking in her head and wouldn’t leave her alone.” The novel underwent minimal editing, so what we read is almost entirely Tina’s original version.

A book that is worth the annotations

If you’re interested in reading more reviews and features on Scandinavian (and other) literature, I’d be happy if you checked out the blog. Thank you! ❤️